In the world of David Armillei, creativity knows no bounds. A legal virtuoso turned documentary producer and music aficionado, David’s foray into writing births a compelling narrative captured in Growing Up the Antichrist: An Experimental Memoir. Through 40 poignant pieces of poetry, he intricately weaves his teenage and young adult years into a collection of emotions, offering a glimpse into a life shaped by passion, confusion, and the relentless pursuit of identity. This complex and unique memoir echoes the struggles of yearning for connection, resonating with readers across generations as they explore self-discovery.

Can you provide a brief overview of your memoir, Growing Up the Antichrist, and what inspired you to write it?

Growing Up the Antichrist is, in many ways, an accidental memoir. Although I’m a practicing attorney, as a side project over the past decade I have produced 11 documentary films and 3 albums. In promoting the creativity of others, I began to wonder about my own creative endeavors and whether they had any merit. From the time I was 17 until I turned 25, I wrote a fair amount of poetry and took numerous poetry-writing classes. I then consigned this material to the dark recesses of my closet basically from the moment I started my first post-graduation job.

Revisiting what I had written years after the fact led me to two inexorable conclusions: (1) I thought my writing held up upon inspection in a way that I was comfortable sharing it with the greater world; and (2) although they vacillated wildly between styles, my poems were virtual diary entries of my thoughts and feelings during a really tumultuous time in my life, and collectively they told my story in an interesting way that was also universal. Pulling these pieces together as a quasi-memoir, with an Introduction that explained the process, really gives the reader a more intimate look into my contemporaneous progression than would otherwise be possible.

Introduce yourself and tell me about what you do.

I’m a Stanford Law-educated lawyer who has practiced in New York and is currently practicing in Los Angeles. Given that I’m also an avid music and movie buff, I’ve started a simultaneous second career as a producer of female-driven documentary films. I’ve been a producer of 10 documentaries so far, with an  11th currently in the works. The documentaries have been reasonably successful: one won Best Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, another one Best Editing at the Sundance Film Festival, and yet another was nominated for a Producer’s Guild Award for Best Documentary. The films have been picked up and shown on PBS, CNN, Netflix, and Amazon Prime, among other sites. In addition, I’ve been an executive producer of 3 albums (two of which are in the tango genre, one of which is jazz).

11th currently in the works. The documentaries have been reasonably successful: one won Best Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, another one Best Editing at the Sundance Film Festival, and yet another was nominated for a Producer’s Guild Award for Best Documentary. The films have been picked up and shown on PBS, CNN, Netflix, and Amazon Prime, among other sites. In addition, I’ve been an executive producer of 3 albums (two of which are in the tango genre, one of which is jazz).

In keeping with my jack-of-all-trades ethos, I was also formerly a minority owner of the Cleveland Guardians (née Indians), unsuccessful entrant into the N.B.A. draft, successful “Lifeline” on ABC’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, and “Boy Friday” to a well-known billionaire. And, for one magical night only, I co-starred in a Broadway play with Princess Leia herself, Carrie Fisher. During my little spare time, I can be found either hiking or accompanying my wife to watch my daughter dance. And yes, even though I don’t have a beard, my hero is Dos Equis’ “Most Interesting Man in the World.”

The title of your book is quite unique. Could you explain the significance of the title and how it relates to the content of your memoir?

In the Introduction, I facetiously attribute the title to “filthy lucre” since something like The Collected Works of David Armillei would cause your eyes to glaze over in sheer boredom. In reality, the title came from a poem I had already written which seemed to sum up so much of what the book is about. The poems are generally about the process of growing up but also experiencing a kind of separation from the dominant group or the milieu of the moment. I’ve always been a bit of an outsider, but never enough of an outsider to fit in with the actual outsiders. In other words, the title can be taken as kind of a reaction to that—i.e., Why am I not fitting in? What am I, the Antichrist? The title is also a nod to the opening line of the Sex Pistols’ classic song “Anarchy in the U.K.”

Your memoir is described as experimental. What does this mean in the context of your book, and how did this approach influence the way you told your story?

Although I’m well read, you would likely characterize me as a music fan more than anything else. I often think in music-based creative terms as opposed to, say, traditional poetry. Accordingly, the memoir is experimental in two respects First, it is akin to a musical “concept album” in which each individual part plays a role in the greater story while standing on its own, but you do not actually see the whole arc until the work is grasped in its entirety. Second, the book is not a traditional memoir; it does not progress from clear Point A to easily digestible Point B in linear fashion.

Upon reading it, you will have a deeper and more unique insight into my thoughts than you would if you read a traditional memoir but likely have no idea of what I was personally doing at any particular moment. My hope is that this makes things both more interesting and more entertaining.

Memoirs often involve a deep level of self-reflection. How did writing this memoir impact your own understanding of your life and experiences?

There were really two levels of self-reflection in creating this book. First, there was my understanding of my life and experiences at the time I originally created the works collected into the book. What I was thinking when I was 19 years old ends up right on the page. The second level of self-reflection was even more interesting for me. I am now 45. I could not (and would not) write in the same way at this moment in my life. I’m not the same person I was when I wrote something at 19; I’ve changed in at least some ways, grown as a person, and/or developed more layers on top of what was once there on the surface. Of course, I still recognize and empathize with the person who wrote the passages in the book.

Re-reading, putting together, and editing everything led to a reawakening in me of those long dormant memories and emotions and, in doing so, made clear to me how far I’ve come while also reemphasizing the validity of my old thoughts. In a way, it is like a musician who writes a song at 23 that he or she still sings in concert 20 years later; you can access the old feeling that initially drove the work while still recognizing that its personal meaning changes over time.

Can you share some of the central themes or messages that you hope readers will take away from Growing Up the Antichrist?

The central theme running through the book involves the burden of nostalgia. As so much ground seemed to be shifting during my late adolescence and early adulthood, a retreat to the past seemed both comforting and confining. As such, a complex—but enduring—hope balances out this respect and distaste for the past, and the ensuing tension ties together the disparate pieces in the book. At one point, I even considered going with the title Kids United Against Nostalgia (another poem in the collection) instead of Growing Up the Antichrist.

Writing a memoir is a journey of self-discovery. Were there any personal revelations or insights that surprised you during the writing process?

There were no major surprises to me during the actual writing process (probably because the pieces of the book, when originally written, were not intended to be “memoir”), but I was certainly surprised by the importance of place when I went back, revised, and edited together everything. The cities in which I lived during the relevant time, such as Charlottesville, Virginia, Palo Alto, California, and Manhattan, provide a critical backdrop for many of the pieces. Franklin, Tennessee, where I grew up, is central to a poem entitled “Preceded in Death” (inspired by a rumor I heard while living there) and the town infuses every aspect of “The Williamson County Trilogy,” a subset of poems that relate the history of Franklin from the 1960s to the late 1980s and mix fact and fiction.

The storytelling style of a memoir is crucial. Can you discuss the specific techniques or elements you used to create an experimental narrative in your memoir?

Readers can correct me if I am wrong, but I’m not familiar with many books that attempt to convey memoir through poetry. That itself is experimental. Moreover, each “chapter” (or poem) is stylistically diverse. I attempt vivid language throughout, but some pieces are way more traditionally accessible than others, and a smattering are defiantly antagonistic to conventionality.

Were there any literary or artistic influences that inspired the style and content of Growing Up the Antichrist?

Various musical genres play a key role in shaping the language and presentation throughout the book. Jazz informs “Saxophone” and “Free Jazz.” Punk Rock provides the basis for “Twenty-One” and “The Souls of Our Dead Heroes.” Country Funk is the literal subject of “Buttered Grits.” The poem “11:05 A.M., AP U.S. History,” is written in Blues format. “Turn on the Bright Lights” is an obvious homage to the band Interpol, and I was listening to The Stone Roses on repeat when I wrote “Amoureuse.” The third line of “The Hollywood Dark” contains a nod to a Pavement song. Finally, the soundscapes painted by Brian Eno during his 1970s heyday are the inspiration for “Kids United Against Nostalgia, Eleven Days Before the World’s End” and “Epilogue” (whose final line explicitly references a 1977 Eno album).

Memoirs often involve a mix of humor, drama, and nostalgia. Can you share some memorable anecdotes or moments from your book that were particularly significant to you?

I went to the University of Virginia for my undergraduate degree. One of my poetry-writing classes there started out well, with the poem that leads off this book, “Saxophone,” receiving a very strong reception from the audience at the beginning of the semester. Then, I decided to write something that I thought was humorous—a poem that appears in this collection as “The Day I Fell Over America After Tripping on Her Bottle of Gin.” That work tries to mix whimsy with a bit of a rant and is similar in tone to Bob Dylan’s writing in his Tarantula collection.

Needless to say, the class seemed to enjoy it, especially when “performed,” but the teacher thought it was an absolutely abhorrent copout and betrayal of whatever talent I have. We even had to have a heart-to-heart coffee outside of class. To try to restore myself in her eyes, I decided to try for the impossible by writing a poem that humanized the 1970s porn star John Holmes, who was likely on my mind because this was around the time the Paul Thomas Anderson film Boogie Nights was released. You may judge for yourself if I succeeded by reading “The Hollywood Dark.”

Growing Up the Antichrist may resonate with readers on different levels. How do you envision your book connecting with a diverse range of readers?

When you are attending school, as I was when the book was actually written, you feel more connected with your peers and generation than any other time in your life. And while each generation has certain distinctive traits, the general process of growing up leads to material commonalities between cohorts. While Growing Up the Antichrist is personal in some ways, it speaks to that more universal age-based and generational experience. A reader would likely recognize himself or herself in a lot of the pieces. And I say “herself” because several of the pieces are written from the perspective of a female protagonist (while conveying my thoughts). Of course, the nice part is that, because each “chapter” is so stylistically diverse, if you don’t like one, just go on to the next. The hope is that you will like or appreciate enough that the book is worth your time.

What would you say is the appropriate age for readers?

Probably about 15 years-old and up. I would expect that the book would appeal mostly to those

in high school, college, and just out of school, especially since those years correspond with my

ages when writing the book and the universal experiences during those years match up with

those that I describe in the book.

Can you talk about your writing process? Did you have any routines, habits, or rituals that aided you in creating this memoir?

Almost every piece was written alone, late at night, using a Word processor, usually in response to a bit of news or significant interpersonal issue I was having. While I love music, few poems were written with anything playing in the background. For good or ill, almost everything appears as it was originally written, with few if any revisions at any point. When I revisited the poems years later, the majority of the changes I made involved combining pieces into one as opposed to any real wordsmithing.

Memoirs often encourage readers to reflect on their own lives. What discussions or self- reflection do you hope your book will prompt among its readers?

I sincerely hope that anyone who bothers to read the book has one of two immediate

reactions: (1) “That was inventive and interesting! I’m going to try doing this myself!”; or (2) “That was awful! I can do better than that!” There’s a reason I cite Michael Azerrad (of Our Band Could Be Your Life fame) and John Doe (of X) on the Dedication page, then quote a verse from Mike D of The Beastie Boys. The technology of the 21 st century has democratized art in a way never previously imagined and torn down both the gates and the gatekeepers. I want others to do, not just reflect.

Are there any future writing projects or literary endeavors you’d like to share, based on the experiences and insights gained from writing this memoir?

In all honesty, this is highly likely to be a classic “one-and-done.” As a litigator, I write a significant amount on an everyday basis and my time spent away from my profession is with my family. I am also very fortunate that my amazing family has basically quelled the inner turmoil that fueled much of this writing. There are very practical reasons most artists, writers, and musicians do their best work while they are young! My future endeavors will likely involve me supporting the creativity of others again, as I have been doing with the documentaries and albums that I have produced over the past decade.

How do you balance the need for self-reflection with the desire to engage readers and make your personal story relatable to a wider audience?

I don’t! It’s all purely accidental. I wrote what I did because that’s what I had to do at that point in time. Other than the previously mentioned experience with “The Hollywood Dark,” I can’t think of a single piece in the book written with an eye towards an audience. The whole enterprise is destined to be niche. I wouldn’t have it any other way. You get only one chance at being truly honest—don’t blow it!

Memoirs can sometimes delve into the subjectivity of memory. How did you navigate this subjectivity when recounting your own experiences?

With something like Growing Up the Antichrist, you simply have to embrace the inherent subjectivity involved. Those were emotional times. A poem like “Twenty-One” was inspired by the best friend I’ll ever have. It’s probably not how he saw himself, but this is my story and my memories, even if they were colored through a certain lens during the moment and made distant now through the fog of time. There can’t really be objectivity in this kind of work.

Do you have some favorite quotes/oneliners from your book?

Since this is really a collection of poetry, the below-listed quotations are drawn from 7 different poems.

First:

wail wop beat and bop jazzmatazz groove blues

awopbopaloobop wham slam bam

but i am so alone,

peering through dim-lit cigarette light,

eyes on alto saxophone

Second:

Once we sipped the chalice,

Held hands in the fields of life anew;

Now all that we had has passed,

Now all that we have is past.

Third:

If I could swim to

The rock that was there,

When I was the lungs,

And you were my air.

Fourth:

May they be strong enough,

And dare to spit

When I could only swallow.

Fifth:

They say that circles will be unbroken,

That better homes await,

And a lord sits by and by,

But all I see is the relentless loss

That aging brings

And the waning echoes

Of a love

Stolen much too soon.

Sixth:

That summer on Grand Street,

Our lives an art installation,

Intoxicating and immortal,

Our time, our city, our sin;

Whatever you can touch,

Can touch you deep within.

Seventh:

The conductor hums

To the rhyme of the track and waits,

In a world distantly sleeping,

Knowing that beauty rejuvenates.

Is there a particular message or piece of wisdom you’d like to convey to potential readers of Growing Up the Antichrist?

As I emphasized previously, Do It Yourself. Be Punk Rock. Make a mark, however small, express yourself, and leave something behind.

Find the author

Growing Up the Antichrist: An Experimental Memoir

“What you are holding in your hands is a curious thing. This book is a memoir, although certainly not a traditional one. Call it an ‘experimental, intellectual memoir.'”

“What you are holding in your hands is a curious thing. This book is a memoir, although certainly not a traditional one. Call it an ‘experimental, intellectual memoir.'”

So begins this startling and compelling collection of 40 pieces that reflect the passion, fears, and confusion of a young man trying to make sense of, find meaning in, and discover his place in the world between the ages of 17 and 25. Full of rhythmic, vivid language, Growing Up the Antichrist uses poetry as a starting point to express profound, maddening, and sometimes hilarious emotional truths about the process of growing up in the early 21st century, grappling with nostalgia, and struggling as an outsider (even among the outsiders). Driven by a complex, but enduring, hope and balancing a respect for and distaste of the past, this “intellectual memoir” goes beyond the author’s own backstory to speak to universal experiences that unite us across the generations.

Purchase Growing Up the Antichrist

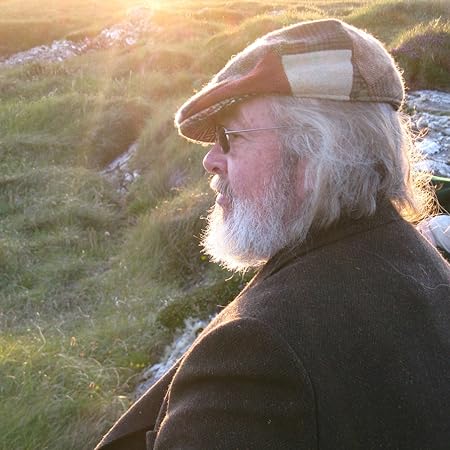

About the author, David Armillei

While pursuing a successful career as a New York—and then Los Angeles—based lawyer, David Armillei began a second career as a producer of female-driven documentary films. After these independent films won multiple awards (including the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival), David decided to follow his own muse and simultaneously pursue yet another path—writer.

Growing Up the Antichrist, his first book, is the result. This experimental, poetic memoir is a collection of 40 pieces that reflect his experience coming of age as a perennial outsider in Franklin, Tennessee, Charlottesville, Virginia, and Palo Alto, California. Driven by a complex, but enduring, hope and balancing a respect for and distaste of the past, the book goes beyond David’s own backstory to address the universal passions, fears, and confusions inherent in growing up.

In keeping with his “jack-of-all-trades” ethos, David was also formerly a minority owner of the Cleveland Guardians (née Indians), unsuccessful entrant into the N.B.A. draft, successful “Lifeline” on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”, and “Boy Friday” to a well-known billionaire. During his little spare time, he can be found either hiking or accompanying his wife to watch their daughter dance.